Safe navigation operator is a syntactic construct mostly found and used in programming languages that offer the object oriented programming paradigm. Safe navigation is needed when navigating properties/methods/children of an object with a need to ascertain that there are no broken pointers.

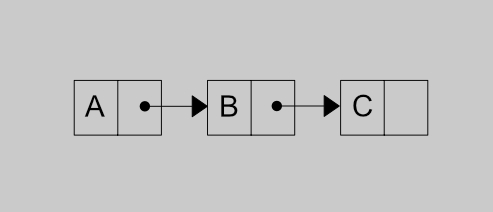

Safe navigation in hashmaps/objects/dictionary is very much similar to the way pointers work in linked lists. For a given linked list. Pointers connect each node in a linked list from the first node to the next node.

Dereferencing is often taught along with linked lists as a way to ensure that there is a valid pointee/reference for every pointer. And as such, I had always seen safe navigation as a form of dereferencing operation. It was odd to me that the wikipedia page of safe navigation didn’t emphasize more on how related they are. Any pointer with a bad reference is known as a bad pointer. In the case of linked lists, that might mean it does not link to any node (data node or dummy node).

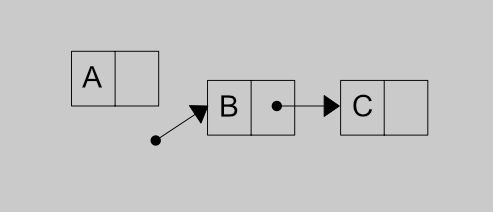

In the figure above, B is still being referenced through a pointer but with no valid pointee. Without proper dereferencing here, we have a broken linked list which can further lead to a broken abstract datatype we may be trying to achieve with the linked list.

I encountered my first safe navigation challenge in ruby before I found an article with a proper breakdown of how to do it right.

We typically would have:

if a && a.b && a.b.c

...

endto safely traverse from object a down to the value of c. But active record comes with a .try() syntax that makes it much prettier.

if a.try(:b).try(:c)

...

endMaybe just better and slightly more concise and not prettier. Really hard to see any beauty here. Ruby eventually came up with a dereference operator that lets us just have:

my_variable = a&.b&.cSimilarly, in JavaScript we can navigate safely with:

if(a && a.b && a.b.c) {

// use a.b.c here

}But as much as JavaScript is bloated with WTFs, there’s some nice parts to it (I can’t name many). JavaScript handles immediate property dereferencing in a much safer way than many other languages. When trying to access an object property we will always get a value, provided the datatype we are hitting is a hashmap object i.e {} or new Object().

We run into problems when we try to access properties that are nested more than 1 level deep. This is because JavaScript will always return a value for object properties and it will return undefined for non existing object properties.

const a = {};

a.b = 'Canada won the nba championship';

console.log(a.c); // undefined

console.log(a.b); // Canada won the nba championship

console.log(a.b.c); // undefinedBecause JavaScript primitive types like String and Array are implemented as objects, we still will be able to access the property c of a without having an error thrown. But when we try any of these:

console.log(a.b.d);

console.log(a.b.c.d);it results in

Uncaught TypeError: Cannot read property 'd' of undefined

Knowing these, I think it’s best to flatten an object whenever we have control of the data in order to have unanticipated error in applications. But sometimes we just need to work with the data available and that might not exactly be the way we want it to be. For such cases, we want to first affirm that we are working with an object type and nonething else. If you use a type system like typescript, you’d probably be safe. But with regular JavaScript, you can assert that you have the expected object type by either peeking to see if the property exist or lazily expecting that the value should be truthy.

const myVarA = a && a.b ? a : {};

const myVarB = a || {};I would go with the former over the latter in most cases as it not only asserts that the data is truthy but also that it’s an object. The property I’m checking for doesn’t really matter at this point because that’s just a shorter way to check I have an object than using other possible options. With the above, we may now use myVarA.

if(myVarA.b && myVarA.b.c) {

// use myVarA.b.c

}Thie two last snippets will give the same results as simply having this but it all boils down to your preference.

if(a && a.b && a.b.c) {

// use myVarA.b.c

}I begin to feel like my code is not readable/clear enough when I have to check so many conditions at once. Hence, I prefer the former break down. There are rumors that JavaScript will introduce dereference operator that will allow us to simply write:

a?.b?.cBut till then, I would still try to use flattened objects where I can. Lodash has utils for this and it also has a .get() object method that behaves like #dig in ruby Hash data type.