There is a common misconception in the web industry that frontend development is easy and has little or no use for algorithms and complex software concepts. This might be the most inaccurate perception for anyone to have. Building user interfaces is infact, exhaustive and can be more complex than backend sometimes.

Graphical User Interfaces have always been fascinating to me, and after observing communities around them and building them for various platforms, I can confirmingly say that it could be the most sophisticated part of building software. For a short background on my past and recent experiences building GUIs, I have built python desktop GUIs with libraries like Qt, GTK, which I’ve blogged about here, and I’ve built themes on KDE Linux that never were shared publicly. As of this writing date, I’ve been building web frontend for 8 years.

In the past 5 years, frontend web development has experienced an upsurge of libraries and frameworks that try to tackle how we address UI engineering. As the web scales, we are gradually getting faced with the challenges of building interfaces beyond the simplicity of declarative HTML and CSS. Some are repulsive to these changes and some of us are open to exploring how they may improve how we build software. This caused huge debates recently that I would not like to be a part of. But as a developer, my mantra has always been to explore new technologies and see how they fit into my workflow, then decide if I should drop them or adopt them; not bash them unreasonably.

Stateful UI engineering is essentially automata-based programming and it can be applied to various forms of programming and engineering. It has been adopted more in electronics and other industries that involve programming hardware and software, but its usage is relatively new in web development. If you’ve used modern JavaScript frameworks, you probably would have used the term state in the context of your component states or perhaps your application state. The use of state in automata-based programming is not too far off that context but it is a little more strict and refined. It is the application of finite automata (a.k.a Finite State Machines) in modeling a software/hardware.

Finite State Machines

Finite state machines is a model with some mathematical origin we don’t necessarily need to know. A finite state machine comprises of a list of states and an initial state that is inclusive in the list. Each of these states can accept inputs to tell them what state to change into. Let’s start with the basic example of traffic lights which have 3 states - Red, Green, and Yellow. Each of these states have a defined state that they can transition into i.e Red goes to Green, Green goes to Yellow, and Yellow goes to Red.

To represent that machine automation flow in a simple JSON format we will have:

{

"initial": "Red",

"states": {

"Red": { "trigger": "Green" },

"Green": { "trigger": "Yellow" },

"Yellow": { "trigger": "Red" }

}

}The trigger is the input that the machine receives to change its state. There can be all kind of inputs to a state machine. It could be a timer that triggers the next state like most traffic lights or it could be controlled by human input. Perhaps a 3-way switch. The major point here is that with these defined possible triggers for each state, a Green state will never trigger a Red because it does not know how to. It knows only to go Yellow when triggered and that makes it much more predictable and reliable. Another example is handbrakes as seen in old stick-shift cars

If you ever drove any of these or had a ride in them, you know you can’t just get in the car and drive when the handbrake is up. The handbrake has to be pushed down before the car moves. A JSON representation of this would be:

{

"initial": "idle",

"states": {

"idle": { "IGNITION_ON": "start" },

"start": { "HANDBRAKE_DOWN": "movable" },

"movable": { "GEAR": "drive" },

"drive": { "BRAKE": "rest" },

"rest": { "HANDBRAKE_UP": "end", "GEAR": "drive" },

"end": { "IGNITION_OFF": "idle" }

}

}We can explore many more examples like its application in bathroom faucets, stopwatch, but it will be nice to have a visual represantation of these state flow we have so far and that’s where statecharts come in.

StateCharts

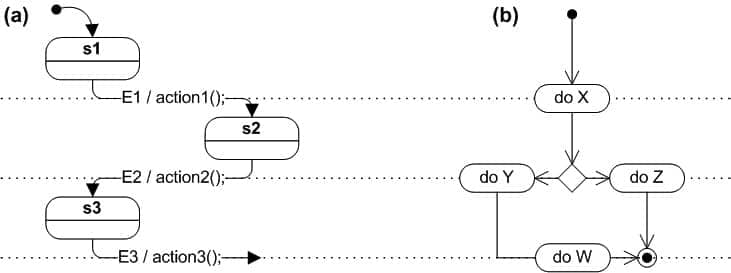

State charts are visual charts of finite state machines as you might have inferred from the name. Traditionally, we learn to use flowcharts to illustrate the top-down approach of an algorithm but wikipedia distinguishes statechart from flowchart with the image:

There is the SCXML</abbr title=“State Chart XML”> (State Chart XML) specification that defines a way to structure a state machine in XML. Our examples above are compatible to this specification but only in JSON format. David Khourshid wrote an excellent JavaScript library called XState that is also based on this specification and lets us apply XState to our applications.

To build a conventional React application with an ajax request we can have the following:

Note: Examples here use the React Hooks API

import React, { useState, useEffect } from 'react';

function App() {

const [posts, setPosts] = useState([]);

useEffect(() => {

axios.get('https://example.com/api').then(result => {

setPosts(result.items);

});

});

return (<>{posts.map(item => (

<div key={item.id}>{item}</div>

))}</>);

}And then we probably get an error: Cannot access property map of undefined. At this point you refactor the code a little to handle loading state so you don’t try to access a method on an array that has not been loaded.

import React, { useState, useEffect } from 'react';

function App() {

const [posts, setPosts] = useState([]);

useEffect(() => {

axios.get('https://example.com/api').then(result => {

setPosts(result.items);

});

});

if(posts.length) {

return (<>{posts.map(item => (

<div key={item.id}>{item}</div>

))}</>);

}

return <h1>Loading...</h1>

}We might get away with this but now we aren’t able to distinguish between when the request is still processing/loading and when there is no post after request is completely loaded.

For a slightly smarter approach we will record our state to know when request is processed and check if the data is empty at that point.

import React, { useState, useEffect } from 'react';

function App() {

// States are: initial, loading, loaded, empty, error

const [ready, setReady] = useState('initial');

const [posts, setPosts] = useState([]);

useEffect(() => {

setReady('loading');

axios.get('https://example.com/api').then(result => {

if(!results.items.length){

setReady('empty');

return;

}

setPosts(result.items);

setReady('loaded');

}).catch(e => setReady('error'));

});

const render = state => ({

initial: '',

loading: 'Loading...',

loaded: posts.map(item => (

<div key={item.id}>{item}</div>

)),

empty: 'No items available',

error: 'An Error occurred'

}[state]);

return (<>{render(ready)}</>);

}This is quite robust and even has an error state and will probably be the most elegant solution without finite state machines but just like I kept discovering earlier that there were base cases I wasn’t covering, I might be missing something here. We often do that as developers and that is how bugs happen. Using XState, the equivalent will be:

import React, { useEffect, useState } from 'react';

import { Machine } from 'xstate';

import useMachine from '../hooks/useMachine';

// All of this machine is predefined even before the code

const feedMAchine = Machine({

id: 'feed',

initial: 'idle',

states: {

idle: { on: { LOAD: 'loading' } },

loading: {

on: {

FETCH_SUCCESS: 'loaded',

FETCH_EMPTY: 'empty',

FETCH_FAIL: 'error'

}

},

loaded: {},

error: {},

empty: {},

}

});

function App() {

const [posts, setPosts] = useState([]);

const [feedState, send] = useMachine(feedMAchine);

useEffect(() => {

send('LOAD');

axios.get('https://example.com/api').then((result) => {

setPosts(result.items);

send(snapshot.items.length ? 'FETCH_SUCCESS' : 'FETCH_EMPTY');

}).catch(e => send('FETCH_FAIL'));

}, []);

const render = state => ({

idle: null,

loading: <p>Loading...</p>,

empty: <p>No item available</p>,

loaded: posts.map(item => <div key={item.id}>{item}</div>),

error: <h1>An Error occurred</h1>

}[state]);

return (<>{render(feedState.value)}</>);

}and we can use David’s XState Visualizer to see a state diagram of the machine in action.

It is a great way to view the action restrictions of each of your states and when a state can or cannot be reached.

As mentioned earlier, there are things that we often might miss when we build user interfaces without state machines even after going through quality assurance and all the various kinds of testing. David explains how the recent facetime bug could have been prevented with state machines in this article. Here is another example of what state machines can prevent.

Notice how when I open a modal within a modal, I lose context of which modal I came from. Closing the inner modal from the comments just closes all the modals, preventing me from viewing content I came from. Now let’s see twitter

Twitter handles this a lot better. It might just be that they covered more edge cases or they have a sought of state machine implemented but this is a much better experience and even very little things like this matter.

Think about how your applications can leverage finite state machines for predictability and stability. It might seem intimidating at a glance but if you struggle to get past that entry phase, it gets easier.